Considerations for using mindfulness as pain relief

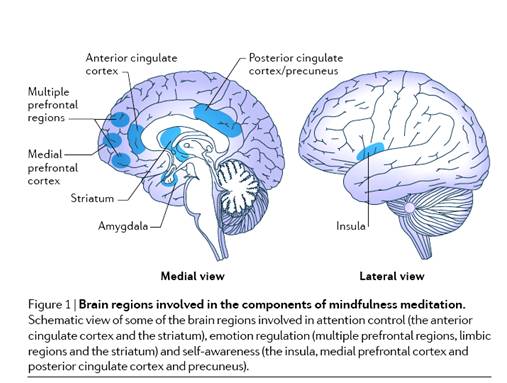

Since we know that meditation strengthens the brain and that pain is always created in the brain, one would think that meditation is good for chronic pain. And quite right – meditation has been shown to help through many neurological mechanisms, as described here, here, and here.

Why do not all pain patients experience relief from their meditation?

It is not uncommon to experience that the meditation techniques do not work or even that the pain gets worse. To make it work for you, you need to consider the following points:

- Understand clearly why you are meditating

- Be aware of any possible post-traumatic stress disorder

- Find techniques that work for you

- Know how to deal with challenges in your meditation

- Take the time to master the techniques

- Practice mindful movement

- Give the techniques long enough for the nervous system to change.

Why we meditate and practice mindfulness

A common belief is that the purpose of meditation is to reach a certain state or becoming completely pain-free. This is not what we are aiming for and misses the greater picture.

The purpose of practicing meditation and mindfulness is this:

To increase the baseline of three attentional skills: concentration, equanimity, and sensory clarity.

As you practice mindfulness, you gradually strengthen these skills. It is a process that takes time, in the same way, that it takes time to build muscle and become strong.

The result from this increased baseline is:

- less pain and suffering

- increased enjoyment and satisfaction

- greater ability to make changes in your life

- greater insight into yourself and your pain

- a less contracted self and self-centred view on life

This increases your quality of life. And over time, this improvement is exponential.

How much do you have to meditate to get noticeable results?

We do not have a clear answer to this. But we have some research results that give us a clue.

In an early study of 51 participants, over ten weeks of daily 30-minute meditation, with chronic pain in either the lower back, neck, shoulders or headache and angina pectoris, 65% showed a reduction of equivalent to or more than 33% in McGill and Melzack’s pain scale. Half showed a reduction of equivalent to or more than 50% on the scale. Read the study here.

Recent research, however, shows that only three days of 20 minutes of meditation show a drastic reduction in pain in a group who were not specifically selected because they had chronic pain problems. Read the study here.

In our experience, you get results with even less effort, even with just ten minutes of sitting practice every day. Nevertheless, the results are in proportion to the effort. And the sitting practice should be combined with mindful movement for lasting results.

Are you suffering from post-traumatic stress?

We are increasingly becoming aware that many chronic pain patients also have post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD. PTSD is a stress-related disorder that may develop after exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence. Sometimes it can also develop from prolonged exposure to emotional or physical stress.

If you suspect that you may have PTSD, or experience that you get worse from meditating, you will have to take precautions. Read more here.

Which techniques are beneficial for chronic pain?

When we use meditation to deal with pain, we can generally divide the techniques into techniques that turn towards the pain and those which one turns away from it.

In the beginning, it is often helpful to turn away from the pain to some degree, but gradually it becomes more and more helpful to focus directly on the pain if possible. In some cases, such as in intense and overwhelming pain, you have no choice but to focus directly on the pain.

Meeting challenges in a fruitful way is about knowing techniques that apply to a given challenge. Therefore, it is useful to know several techniques and to practise them regularly so that you know what to do if a challenge arises.

Basic meditation techniques for pain relief

- Focus on emotions

Focus in: Turn towards

Since pain, in most cases, is related to emotions, it is beneficial to work directly with them. Anger, fear, sadness, worry and shame are not uncommon reactions to lasting pain. This technique is an example of turning towards, facing and opening up to the pain and discomfort it causes. - Focus on the physical experience of the pain

Focus Out: Turn towards

It may seem strange, but it can be constructive to meditate directly on the pain. You can expect the experience of the pain to increase when you focus on it, but that is not dangerous. Rather, you will gain insight into the fact that the pain is constantly changing, both in strength and location in the body. And by having less resistance to the pain and more acceptance, the pain becomes less threatening and thereby decreases. - Focus on the experience of rest

Focus on rest: Turn away.

Stress often contributes to persistent pain, and with mindfulness, we can learn to reduce the experience of stress.

Stress can be understood as a crisis mode and causes several parts of our body to turn off for a while – the digestion, the genitals, and parts of the brain. The blood flow changes so that the limbs get more blood, while the torso gets less.

We also get special holding patterns in the muscles, which prepare us to protect ourselves from something threatening. We raise our shoulders, prepare to hunch down and brace ourself, bite our teeth together, etc.

By focusing on resting states, we learn to find faster relaxation in everyday life. - Focus on external experience

Focus Out: Turn away

This is another way to turn away from the pain. Instead, we turn to external sensory experiences, such as sounds and music. As in all techniques, we train the attentional skills of concentration, equanimity and sensory clarity. Indirectly, it helps us to down-regulate the parts of the brain that help to provoke a pain response. - Practice friendliness towards yourself

Friendliness meditation: Turn away and towards

It is not uncommon for chronic pain patients to also suffer from self-criticism, feelings of low self-worth and perfectionism. Friendliness meditation, also called loving-kindness meditation, is a good method to work directly with our relationship to ourselves. Often this is done by also working with the relationship to others, and this can further help to transform the relationship to the pain itself.

Mindfulness in motion

Being in motion is often pain-relieving in itself, and also teaches us to have a relationship with the pain that makes it seem less threatening. When we meditate as we move, meditation is central. It is common to do Focus Out, but in principle, almost all meditation techniques can be used in motion as well.

Mindful movement methods such as the Feldenkrais method, Hanna Somatics, yoga, taichichuan and qigong are suitable for this, but also dance, stretching or regular morning gymnastics. I would also recommend having a look at a relatively unknown method that is particularly suitable for treating pain: Edgework.